Rethinking the Death Penalty dilemma in Nigeria

By Judiciary Reporters, News Agency of Nigeria (NAN)

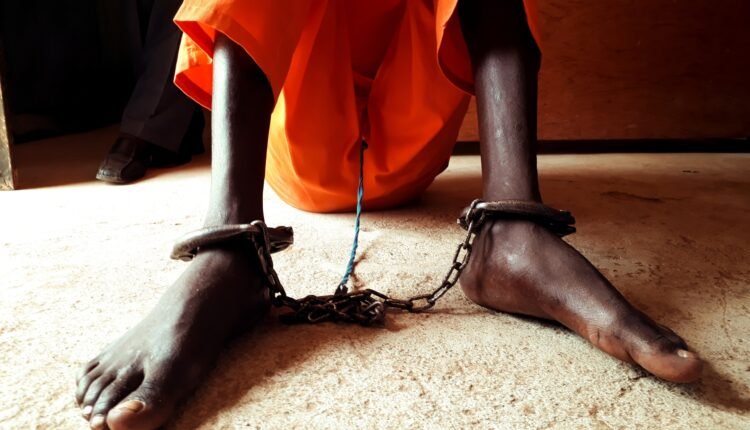

With hundreds of inmates languishing on death row and governors increasingly reluctant to sign execution warrants, Nigeria finds itself caught between legal duty and moral conscience.

Although capital punishment remains enshrined in the Constitution, a growing number of legal experts, human rights advocates, and policy stakeholders are calling for sentencing reforms.

This includes proposals to replace the death penalty with life imprisonment, which many stakeholders consider a more humane and legally sustainable alternative.

Under Nigerian law, state governors have the constitutional responsibility to sign death warrants for convicts sentenced to capital punishment.

This authority forms part of their role as heads of the executive arm of government and underscores their responsibility to ensure that justice is carried out.

In addition, governors are empowered to grant clemency, including pardons or commutations, which may ultimately halt an execution.

Nevertheless, international attention has remained fixed on Nigeria’s death penalty policy.

The UN General Assembly has repeatedly called for a global moratorium on executions, with the long-term goal of abolishing capital punishment altogether.

Consequently, Nigeria has come under pressure from international human rights bodies to address its continued application of the death sentence.

Although Nigeria is a signatory to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which provides guidance on the application of the death penalty, it has yet to abolish capital punishment formally.

However, there is a de facto moratorium in place, meaning executions are no longer carried out, even though the law allowing for capital punishment remains active.

As a result, several observers and advocacy groups have urged the government to ratify the Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR, which commits signatory nations to abolishing the death penalty.

According to the Nigerian Constitution, the decision to sign a death warrant lies solely with the governor of each state.

This discretion allows governors to either approve or delay execution, even after all legal appeals have been exhausted.

While the law permits executions, the practical decision often reflects personal convictions, political calculations, or concerns over human rights.

Since the country’s return to democracy in 1999, executions have been rare.

For instance, the execution of Sani Yakubu Rodi under Sharia law in Katsina state in 2002, and a series of hangings carried out in Edo during Gov. Adams Oshiomhole’s tenure between 2012 and 2016, remain among the few documented cases.

These sparse instances underscore Nigeria’s status as a country where the death penalty exists in law but is seldom enforced in practice.

Meanwhile, legal practitioners across the country are divided over the morality, relevance, and enforceability of capital punishment.

The growing reluctance by governors to sign execution warrants has prompted renewed debate about the future of the death penalty in Nigeria.

Speaking to the News Agency of Nigeria (NAN) recently, Mr Stephen Oluebube, a legal expert, said religious beliefs and misconceptions about official responsibilities may be discouraging governors from signing execution orders.

According to him, many religions, especially Christianity and Islam, oppose the unjust taking of human life.

“Hence, many governors think that by signing execution warrants, they are personally responsible for the killing.

“Most of them fail to understand that signing such warrants is a constitutional act of the office, not of the individual, ” he explained.

Oluebube further argued that although human rights groups have consistently called for abolition, Nigeria might not yet be ready to completely discard the death penalty.

“Its existence has deterred many from engaging in extreme violence,” he said.

However, another lawyer, Mr Sydney Nwachukwu, held a different view.

He insisted that only God has the right to take life, noting flaws in the judicial process.

“Our judges are human and prone to errors. Many murder convicts may not have the financial resources to pursue appeals up to the Supreme Court,” he said.

He added that he does not support the death penalty and believes the system is too flawed to justify irreversible punishments.

“Our police investigations and judiciary are corrupt and compromised. The entire framework requires an overhaul”.

In a similar vein, Mr Damian Nwankwo described capital punishment as a legal penalty that is rarely enforced because of governors’ increasing moral and ethical reservations.

“Although courts pronounce death sentences, the burden of implementation rests on governors’ consciences,” he said.

Nwankwor listed other reasons for the reluctance, including pressure from civil society, fear of judicial error, and political ramifications.

“Human rights organisations have consistently campaigned against the death penalty. Many governors fear backlash from religious leaders, advocacy groups, and the international community,” he explained.

He also expressed concern over the possibility of wrongful executions, which could spark national outrage.

“For politicians mindful of public opinion and future ambitions, the risks of signing far outweigh the benefits,” he added.

Nwankwo stressed that Nigeria appears to be operating an unofficial moratorium.

“Many death sentences are commuted to life imprisonment, or inmates remain on death row for years without resolution”.

Read Also: NAFDAC renews crackdown on counterfeit drugs

To address this dilemma, Nwankwo called for urgent legal and constitutional reforms.

“We must review the laws governing capital punishment and the governor’s role. Our current legal framework is outdated and misaligned with global human rights standards,” he said.

He urged lawmakers to replace the death penalty with life imprisonment without parole for the most serious offences.

According to him, Nigeria is a signatory to key international treaties that discourage capital punishment, including the ICCPR and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

He added that the reform would reflect Nigeria’s commitment to human rights and improve prison conditions by offering avenues for commutation or retrials.

“Thousands of inmates languish in terrible conditions on death row. We must create pathways for rehabilitation, not indefinite suffering”.

Another lawyer, Mr Thaddeus Mbalian, said Nigeria’s international treaty commitments discourage executions.

He called for internal law reform to bring the country in line with international expectations.

However, he noted that Nigeria’s dualist legal system, where treaties do not automatically override domestic laws, complicates the process.

“Executing judicial decisions has become a challenge. To avoid delays and confusion, we should abolish the death penalty entirely,” Mbalian said.

Similarly, Mrs Queendoline Ekong argued that the death penalty should be removed from Nigeria’s statute books due to long-standing implementation difficulties.

Also, Mr Yakubu Dauda, another legal voice, pointed out that the Federal Government lacks the authority to compel governors to carry out executions.

“Under Section 212 of the 1999 Constitution, only state governors; after consulting their State Advisory Councils on Prerogative of Mercy, can sign death warrants,” he said.

“The president cannot interfere or compel a governor to sign a death warrant. It is a purely state-level constitutional mandate,” he added.

He noted that some governors choose to commute death sentences to life imprisonment instead of signing execution orders, often in response to public and international pressure.

NAN investigations reveal that only three governors have signed death warrants since Nigeria’s return to democracy.

In 2006, Gov. Ibrahim Shekarau of Kano reportedly signed for the execution of about seven inmates.

Gov. Adams Oshiomhole of Edo signed in 2012 for two prisoners who were later hanged.

Gov. Godwin Obaseki, also of Edo, signed for three inmates in 2016, and those executions were carried out shortly after.

As the national conversation continues, legal experts agree that the current state of capital punishment in Nigeria is unsustainable.

They insist that the absence of executions, albeit legal provisions, contributes to public uncertainty and weakens confidence in the justice system.

They however recommend replacing the death penalty with life sentences for the most heinous crimes and aligning domestic law with international best practices.

Without clear policy direction, they warn, the country risks further erosion of justice and continued ambiguity over the fate of those on death row. (NAN)